Author: Richard Pountney (SIG Leader)

‘The officer and the office, the doer and the thing done, seldom fit so exactly, that we can say they were almost made for each other’ [1]

We all know the saying about square pegs and round holes, and how they mis-align, but it is also true that round pegs will fit into (some) square holes. I am reminded of this when I am working with postgraduate researchers (PGRs) who are looking for a methodology. They are often very clear on the problem, and the problem space. Sometimes they haven’t yet problematised their object of study. By this, I mean that new(er) researchers may be stuck at a point where they are not yet ready to give up on things they take for granted – as Pat Thompson explains, ‘problematising simply means making something problematic, not taking it for granted, questioning assumptions, framings, inclusions, emphases, exclusions‘. Before I go on to unpick some of the implications of this, I should acknowledge that early stages of postgraduate research are subject to all of the uncertainties and doubts that we all face when starting research, and that PGRs look to their supervisors to guide them. And, I remember the frustration when my supervisors bounced this back to me: ‘… what do you think, Richard?’ Faced with this, it is not surprising that some researchers go searching for that square hole to put their round peg in.

I should say that there are a lot of square holes out there, and some are more signposted and available than others. Sometimes these square holes are contextually favoured – they dominate the discourse in doctoral schools and they become the measures of success in research. A straw poll of education professors and doctoral supervisors in my own institution show that socio-constructivist, sociomaterial, and ethnomethodological interests predominate. Well, hats off to these colleagues, of course, and their eminence in their research areas is well deserved. But, think about that for a moment. The established community of researchers is led by research leaders, each with their own repertoire of interests and problem spaces, creating a reservoir of intellectual capital and resources. This is the well that supplies the drinking water to researchers. The struggle over these resources is more than who in the institution is named in the Research Excellence Framework (a key factor in funding for research) – it also affects how doctoral scholarships are determined, how supervisors are allocated to new doctoral students (who, often, are yet to decide on a research methodology), and how funding is allocated. Therefore, while I would hesitate to label these research leaders as gatekeepers, it is not much of a stretch to suggest that there is potential for reproduction of the status quo in this scenario.

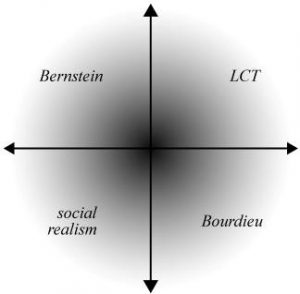

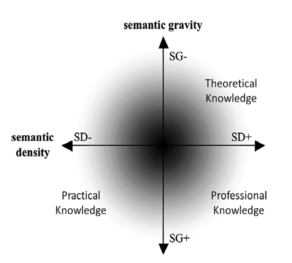

So what has this to do with this SIG ? The knowledge in education field is referred to as a ‘coalition of minds’ – the intersection of the ideas of Pierre Bourdieu, Basil Bernstein, and Karl Maton, referred to as (Social) Realism (see the post Waving not Drowing). This field has eminent and influential researchers, including Professors Michael Young, Johan Muller, Leesa Wheelan and Elizabeth Rata (the Cambridge Bernstein Group) and Karl Maton (Legitimation Code Theory), who have published a significant corpus including hundreds of doctoral studies that have used these theories (see, for example, the database of LCT publications here). These theorists are linked with international centres of excellence associated with this SIG (for a list see About) and there is a growing interest in these ideas in the Sheffield Institue of Education (and hence this SIG), but this is not without its own struggle. Over what, you might ask?

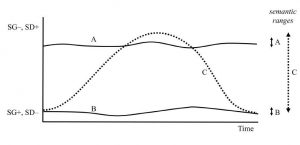

It is perhaps a given that any curriculum has knowledge, of some kind, at its foundation and that the acquisition of knowledge is a ‘key feature that distinguishes education (general or vocational) at any level from all other activities’ (Young, 2003: 553). However, this does not sit comfortably with those who draw on understandings of the curriculum as social practice (Brown and Duguid, 2001), and who criticise curricula that are seen as knowledge-based (Pinar, 2006). In this sociological point of view the word knowledge is reserved for what is collectively endorsed or granted with authority by groups of people (Bloor, 1991). Edwards and Usher (2001: 280) refer to the ‘unruliness’ of knowledge owing to the lack of rules and the sense that it is ‘up for grabs’ epistemologically. This view of knowledge as constructed and contested downplays the notion of disciplines as bodies of canonical knowledge to be transmitted in favour of generic and transferable skills (ibid). Gibbons et al. (1994), for example, argue for a mode 2 form of knowledge that is ‘trans-disciplinary’, context-driven and problem-focused. This contrasts with the traditional, mode 1, form of knowledge that is academic and discipline based. However, there is a value-laden implicit message here that mode 2 knowledge should replace mode 1 in which for ‘mode 1 read stuffiness; for mode 2 read avant-garde and glitzy’ (Barnett, 2009: 431).

One outcome of this purely social, and socialised, approach to curriculum and pedagogy is the situation where ‘the mantra of ‘learning how to learn’ arises … [in which] Knowledge recedes from view’ (ibid 430). This prevailing aversion to knowledge, that to rely on knowledge is to be ‘didactic, a didact, or even worse a pedagogue’, is, Barnett suggests, held by academics both ethically and pedagogically. Maton (2007; 2013; Moore and Maton, 2001) refers to this as a kind of knowledge blindness, or at the least a ‘blind-spot’, that limits knowledge structures being theorised in empirical research. Young (2008: 14) goes further to suggest that we need insights into knowledge structure in the curriculum to distinguish between ‘knowledge of the powerful’ and ‘powerful knowledge’ – in terms of what it tells us about knowledge itself – e.g. the fact that some curriculum knowledge, such as esoteric knowledge, is higher status (Beck, 2013).

Therefore, if you are someone who is thinking about researching curriculum and/or professional learning there are three reasons, drawing on Wheelahan (2010), I would like to give you as to why knowledge is important in your study:

The first is that the notion of knowledge and its acquisition has implications for learning and teaching. It resonates with Meyer and Land’s (2005) work on threshold concepts and knowledge that students (and teachers) find ‘troublesome’. The implications of this are echoed by Donald’s (1986) study of knowledge concepts in HE courses, including physical science, social science, applied disciplines and humanities. She identifies disciplinary differences occurring at four levels: in the nature of the concepts used; in the logical structure of the discipline; in the truth criteria used; and in the teaching methods employed in the discipline. Her study indicates that students in social science subjects (horizontal and segmented knowledge structures in Bernstein’s terms) were required to have a greater ability to make inference, while physical science (hierarchically structured) require less inference. This focus on knowledge and concepts matters, therefore, because it aims to bridge the gap with understanding and skills by emphasising that constructivist approaches, which aim to ‘scaffold’ learning, are important as a means to an end (i.e. learning), not the end in itself (the process of learning).

The second reason why knowledge is important is because of the argument that teachers have epistemological beliefs, related to their disciplinary understandings, about knowledge and knowing (Hofer and Pintrich, 1997) and that these beliefs shape how the discipline is taught and what is required of students (Buehl and Alexander, 2001). These beliefs range from naive to sophisticated, involving beliefs of whether ability to learn is innate, how knowledge is acquired, the source (and authority) of knowledge, its certainty, and its inter-relatedness (Schommer, 1993; 1994). Where these epistemological understandings are underdeveloped or unclear this can lead to students’ surface learning: this also has an effect on how teachers develop their pedagogy that in turn influences learners’ own epistemological beliefs (Nielsen, 2012). Attention to knowledge, therefore, can offset the ‘pedagogic imperative’ that otherwise restricts teachers’ thinking to the realities of the classroom.

The third reason is that attempts to deny knowledge as important in the curriculum also deny the social basis of knowledge as a condition of its own possibility (Young, 2013). Furthermore, it excludes the possibility of something other than itself, as a ‘doxic’ experience of the world (Schiff, 2009). Knowledge blindness (Maton, 2007; 2013; Moore and Maton, 2001), therefore, opens the door for those, including curriculum reformers, who seek to develop ideological conceptions of the curriculum, such as competence-based training and genericism (Wheelahan, 2010; Young, 2008), and to project a prospective neo-conservative identity for children and future citizens (Beck 2012). Social realism, on the other hand, promotes the idea of ‘powerful knowledge’ (Young, 2008), and the potential to ‘regenerate’ the curriculum (Beck, 2013).

The reasons I give above make the case for using sociology of knowledge concepts in researching curriculum practices and are aligned with the notion that the concepts enable the identification of the problem as well as its explanation, while the empirical data provides the illustration, even evidence, of both problem and explanation. As Rata (2012) advises us, such a methodology is within the Kantian rationalist tradition where the “united operation” of concepts and content (Kant (1781, p. 69) avoids both the idealism of concepts alone and the restrictions of empiricism.

I argue, therefore, that a realist, or conceptual, methodology of curriculum and professional learning is a round hole for researchers who have round pegs shaped by their problematisation of their objects of study. Of course researchers might still decide to use the square holes more-readily available to them, possibly because of their concern for complexity – and their research projects will fit in very nicely. My concern is that on the completion of their studies they may have a beautiful rendering of the problem, but still have complexity.

So, yes, research is complex – but need it be complicated? I will return to how a realist, conceptual methodology can simplify problematics and what this entails in a later post.

To be continued …

[For opportunities in doctoral scholarships in curriculum studies in 2020-21 see details here]

References

[1] Smith, Sydney, Elementary Sketches of Moral Philosophy, Delivered at the Royal Institution, in the Years 1804, 1805, and 1806 (London, 1850), p. 111, quoted in Bell, Alan, Sydney Smith: A Life (Oxford, Oxford UP, 1980), p. 58.

Barnett (2009) Knowing and becoming in the higher education curriculum, Studies in Higher Education, 34:4, 429–440

Beck J. (2012) Reinstating knowledge: diagnoses and prescriptions for England’s curriculum ills, International Studies in Sociology of Education, 22(1), 1–18

Beck, J. (2013). Powerful knowledge, esoteric knowledge, curriculum knowledge. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(2), 177-193.

Bernstein, B. (2000) Pedagogy, symbolic control and identity: Theory, research, critique. Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield

Bloor, D. (1991) Knowledge and social imagery. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Brown, J. S., and Duguid, P. (2001) Knowledge and organization: A social-practice perspective. Organization Science, 12(2), 198–213

Buehl, M. M., & Alexander, P. A. (2001). Beliefs about academic knowledge. Educational Psychology Review, 13(4), 385-418.

Cook, S. D., & Brown, J. S. (1999). Bridging epistemologies: The generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing. Organization science, 10(4), 381-400.

Donald, J. G. (1986) Knowledge and the university curriculum. Higher Education, 15(3–4), 267–282

Edwards, R., and Usher, R. (2001) Lifelong learning: a postmodern condition of education? Adult education quarterly, 51(4), 273–287

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P., and Trow, M. (1994) The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies.

Hirst, Paul H., ed. “Curriculum integration.” In Knowledge and the curriculum. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1974

Hofer, B. K., and Pintrich, P. R. (1997) The development of epistemological theories: Beliefs about knowledge and knowing and their relation to learning. Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 88–140

Kant, I. ([1781] 1993) Critique of pure reason. London, Everyman

Maton, K. (2007) Knowledge-knower structures in intellectual and educational fields. Language, Knowledge and Pedagogy: Functional Linguistic and Sociological Perspectives, 87–108

Maton, K. (2013) Knowledge and Knowers: Towards a Realist Sociology of Education. London: Routledge

Meyer, J. H., and Land, R. (2005) Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 373–388

Moore, R. and Maton, K. (2001) Founding the sociology of knowledge: Basil Bernstein, intellectual fields and the epistemic device. In A. Morais, I. Neves, B. Davies and H. Daniels (Eds.), Towards a Sociology of Pedagogy: The Contribution of Basil Bernstein to Research, New York, Peter Lang: pp. 153–182

Muller, J. (2009) Forms of knowledge and curriculum coherence. Journal of Education and Work 22: 205–26

Nielsen, S. G. (2012). Epistemic beliefs and self-regulated learning in music students. Psychology of Music, 40(3), 324-338.

Pinar WF. (2006) The synoptic text today and other essays: Curriculum development after the reconceptualisation. New York, Lang

Rata, E. (2012). The politics of knowledge in education. British Educational Research Journal, 38(1), 103-124.

Schiff, J. (2009) The Persistence of Misrecognition. In Political Theory Workshop (Vol. 12) [Online at: http://ptw.uchicago.edu/Schiff09.pdf. Visited 30/6/13]

Schommer, M. (1993). Comparisons of beliefs about the nature of knowledge and learning among postsecondary students. Research in higher education, 34(3), 355-370.

Schommer, M. (1994). Synthesizing epistemological belief research: Tentative understandings and provocative confusions. Educational psychology review, 6(4), 293-319.

Wheelahan, L. (2010) Why Knowledge Matters in Curriculum: A Social Realist Argument. Abingdon, Routledge

Young, M. (2003) Durkheim, Vygotsky and the curriculum of the future, London Education Review, 1(2)

Young, M. (2008) Bringing Knowledge Back In: From Social Constructivism to Social Realism in the Sociology of Education, London and New York, Routledge

Young, M. (2013). Overcoming the crisis in curriculum theory: A knowledge-based approach. Journal of curriculum studies, 45(2), 101-118.