Author: Richard Pountney, SIG Lead

This article was published in the BERA Research Intelligence Special Issue #148, International Perspectives on the Curriculum: Implications for teachers & schools’, Autumn 2021, edited by Richard Pountney and Weipeng Yang, convenors of the BERA Curriculum, Assessment and Pedagogy SIG.

In an era of sweeping changes, accelerated by a pandemic that is driving nations to make rapid responses in their systems of schooling, the question arises, how is the fundamental purpose of education being altered? The realities of global effects on work, travel, and access to learning have brought home a key message: that national dilemmas cross boundaries and are shared. One such concern is for the climate and the future of the planet itself and our place on it. How can the curriculum itself be the means of reshaping and giving voice to this?

Activist movements have garnered significant global attention on a range of societal issues, involving collectives of citizens coming together (Niblett, 2017). However, the role schools should take on climate education is often contested by curriculum stakeholders, who tend to disagree not just on learning about the climate, but also about the individual and collective response that might be possible. Here, the curriculum delivered in schools serves to either maintain or interrupt the status quo, and any interruption begs the question of whether to change the curriculum, or to see curriculum as change itself. The latter position argues for a curriculum that is the source of, and vehicle for, change through transformative activist curricular movements (Gorlewski, & Nuñez, 2020). Below I introduce two cases that illustrate this division.

The first case, the Climate Action Project (CAP), exemplifies a curriculum approach to teaching climate change in schools that is taken by organisations, such as Take Action Global. The aim is to address how to teach environmental awareness and provide resources and initiatives for schools to get involved. CAP, founded by Koen Timmers in 2017, held a six-week event in October 2020 focused on climate change, involving 2.6 million young people across 140 countries. Children worked collaboratively on solutions and meaningful action, to stimulate positive thinking about change. Working with Ministries of Education in 15 countries, the project created a curriculum for climate change, co-authored with the World Wildlife Fund International. Teachers became part of a networked community of practice and were guided by facilitators, and the project made an impact in many countries, culminating in a 2020 webinar “Climate Action Day” hosted by Sir David Attenborough, involving scientists from across the world. While, this approach might be characterised as an intervention, in that the effect on the curriculum may not be permanent, it raised awareness of the need for curriculum action.

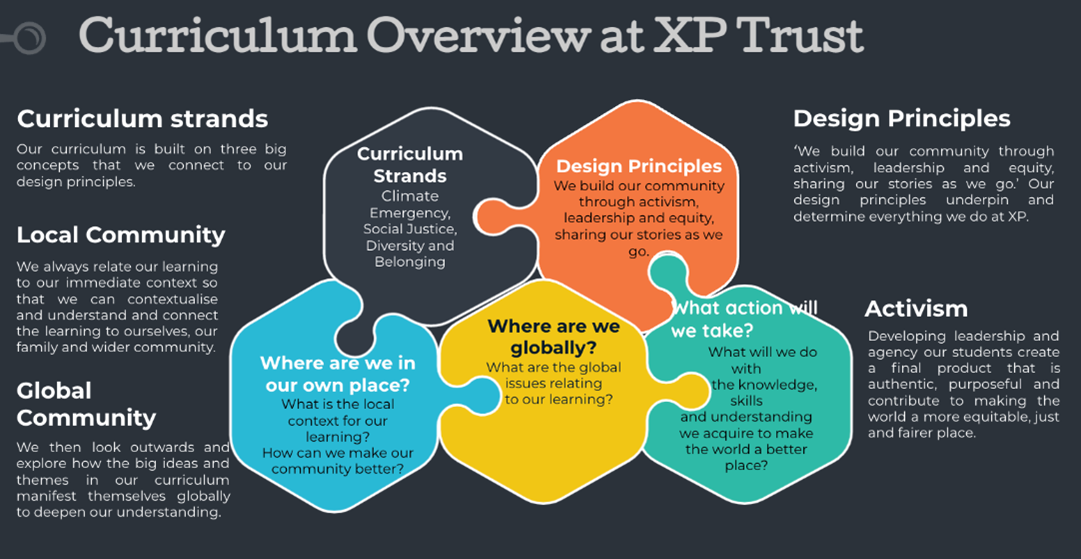

The second case is one of curriculum integration, in which schools make longer-lasting and more far-reaching changes to what is taught. XP in Doncaster, UK, is a small multi-academy trust, that follows a curriculum based on cross-curricular, project-based learning, where the curriculum is taught via ‘expeditions’, that last 6-12 weeks. In recent curriculum planning, the schools have decided that climate change is an existential threat and an imperative part of the curriculum. They have identified ‘Climate Emergency’ as one of 3 key ‘strands’ in their curriculum (see Figure 1), and teachers have designed expeditions in all years of the secondary schools that address this theme.

One expedition, ‘RE:VOLT’, in year 8, has the guiding question, ‘Could harnessing the power of the wind uplift developing countries?’ Taught through case studies and field work, the final product is the design and testing of wind turbine blades. Students build circuits that transfer the energy stored first in the wind into something useful – light. They also study an inspirational extract by William Kamkwamba about ‘The boy who harnessed the wind’, in which he describes how his curiosity about dynamos led to him making his own wind turbine for his home in Malawi.

However, the idea of climate emergency as a problem that schools and the curriculum need to respond to is challenged by a view of environmental and climate change as distant or future problems, rather than immediate and local ones. Adding to this, is the complication of climate change as a ‘socioscientific issue’, one that requires specialised scientific knowledge and a critical interpretation of the issues (Hodson, 2020). Here, the preparation of students to learn through and from an integrated, or embedded, environmental curriculum approach invokes the idea of citizens informed by a curriculum that is deep, as well as broad. It raises the question of whether education is preparation to take action that emerges, not from a common-sense understanding of everyday life, but rather from a deep political understanding of the world – one that is underpinned by a level of civics knowledge that provides the intellectual basis for engaging in public discussions and planning citizen action (Jerome, 2018).

Returning to the question of the purpose of education, the ability to deal with cultural objects and to self- and co-determine one’s place in the world is closely related to an active curriculum. The European notion of Bildung arises here, as the formation of the educated person in which the learner asks what a prospective object of learning can and should signify to them, and how they themselves can experience this significance (Hudson, 2007). While the case for schools being responsible for developing the knowledge, skills and dispositions for active citizenship remains to be made, what is clear is that teachers who are active in curriculum and policy creation are empowered as teachers and activists. This posits the school as both democratic and open, in the sense of having boundaries that are fluid and permeable to the concerns of society (Pountney and McPhail, 2019). The open flow of ideas is thereby, important in order that people can be as informed as possible, in which they have faith in the individual and collective capacity of people to solve problems, and, ultimately, that they have concern for the welfare of others and the common good. This rests on the principle that democracy is not so much an ‘ideal’ to be pursued as an ‘idealized’ set of values that we must live by and that must guide our lives. Moreover, to achieve this teachers need to nurture democratic and caring classroom communities, where ‘to be a teacher is to be actively engaged in a social movement that is shaping the future of our society and our world’ (Gorlewski & Nuñez, 2020, p.14).

Disclaimer: Richard Pountney is Chair of Trustees of the XP Schools Trust and leads the Curriculum Committee as a director.

References

Gorlewski, J., & Nuñez, I. (2020). Activism and Social Movement Building in Curriculum. In Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Education. https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-1421

Hodson, D. (2020). Going beyond STS education: Building a curriculum for sociopolitical activism. Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education, 20(4), 592-622.

Hudson, B. (2007). Comparing different traditions of teaching and learning: What can we learn about teaching and learning?. European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 135-146.

Jerome, L. (2018). What do citizens need to know? An analysis of knowledge in citizenship curricula in the UK and Ireland. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 48(4), 483-499.

Niblett, B. (2017). Facilitating Activist Education: Social and Environmental Justice in Classroom Practice to Promote Achievement, Equity, and Well-Being. Research Monograph, 66, 1-4.

Pountney, R. and McPhail G. (2019) Crossing boundaries: exploring the theory, practice and possibility of a ‘Future 3’ curriculum, British Educational Research Journal, 45: 483-501 DOI 10.1002/berj.3508