We take it for granted. It’s been described as the closest thing we have, now, to a national religion. It’s probably become politically untouchable. We have all either depended on it or had a family member or close friend who has depended on it. It remains a tribute to the genuinely visionary political leadership of Nye Bevan, minister of health in the post-war Labour government. Within three years of the end of the Second World War which had almost bankrupted the country, the government created a national health service, free at the point of use and funded from general taxation. In Never Again, his superbly readable account of Britain between 1945 and 1951, Peter Hennessy says simply that “the fifth of July 1948 was one of the great days in British history….it was a day that transformed like no other before or since the lives and life chances of the British people”. And so, this week, it is seventy years old.

Seventy years is long enough for us to take something for granted, but it’s really not very long. I can remember the stories my grandparents told of the patchwork of healthcare in the pre-NHS days, the mix of provision, the deep fear that an illness would mean an unpayable bill. Earlier this year, my daughter who works in New York was diagnosed with a serious illness. When she phoned us to tell us the results of tests which had confirmed the illness, my first question to her was ‘is this covered on your health insurance?’ It was. If it hadn’t been, she would now be looking at a bill for over $284,000. It’s not something we have had to worry about for two generations in the UK, but it was a desperate worry for our grandparents and their parents in the complex patchwork of pre-NHS health care. Professor Rudolf Klein, the great social policy analyst, called it “the only service organised around an ethical imperative”.

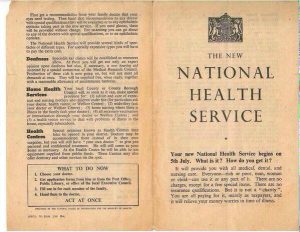

We shall be celebrating the NHS’s seventieth birthday at Hallam with a series of events on Thursday, in the Heart of the Campus building at Collegiate. There’ll be a display of archive materials including health education posters exploring changing attitudes to public health – and especially smoking – and artefacts including uniforms and equipment from noon, a series of talks and presentations between noon and 2 pm and afternoon tea between 2 and 4 pm. Our guests will include Pat Cantrell, former Deputy Chief Nurse at the Department of Health, Shirley Rowe, former nurse and Sheffield School of Nursing Tutor, and Drs Tony and Jill Bethell, both former local GPs. There’ll be bunting out and the SHU choir will be on hand to sing songs from the 1940s and 1950s.

Sheffield Hallam University is one of the country’s major providers of healthcare education – educating more new members of the NHS workforce each year than any other provider in England and supporting post-experience learning across the country. The pattern and provision of our health education is sophisticated and complex – our novice health professionals learn in environments which provide them with real world-type wards and clinics, and, increasingly, technology mediated learning. The ways in which our health provision is now structured mirrors the ways in which health care has changed since the establishment of the NHS: increasingly focused on evidence-based medicine, on the exercise of complex professional judgements in providing personalised healthcare, on the place of technologies and digital health in the provision of care and on inter- and cross-professional working.

The healthcare challenges of the twenty-first century are not the healthcare challenges of the 1940s, and even within a few years of its foundation, politicians were grappling with the consequences of the NHS’s success – increasing demand and rising bills. Now, an ageing population, increasingly sedentary lifestyles, complex interlocking chronic conditions all pose difficult challenges for a national service. Beyond the University’s vital role in education, healthcare research at the University is exploring some of the most difficult contemporary questions: on cancer care, on childhood obesity, on the ways in which we can transition from treating illness to promoting wellness, on the relationship between population health and population wellbeing. But we approach these questions in the context of a nation in which access to healthcare is secure for everyone, wherever they live and free at the point of use. It will, predicted Bevan, last as long as “there are folk left with the faith to fight for it”.

Peter Hennessy closes his account of the establishment of the NHS by saying “it was a statement of intent, a symbol of hope in a formidable, self-confident nation. That should not be forgotten in…the trials and tribulations and the often fractious politics of healthcare….The NHS was and remains one of the finest institutions ever built by anybody anywhere”.

Which is worth a party.