ICfE > Open Day > Transition into HE > Level 4 > Level 5 > Level 6 > Level 7 > Applied Learning > Career Readiness > Local Market Intelligence > Digital Skills for Employability > Enterprise > Feedback

Career Readiness

What is Career Readiness?

Career Readiness is the model of career learning adopted by Sheffield Hallam, which aims to support learners to “reflect on themselves and what they have gained through their academic and wider university experience, to understand and research opportunities for themselves and make career choices, and prepare to obtain, and succeed in, their next steps” (AGCAS, 2019). In other words, career learning helps students to “proactively navigate the world of work and self-manage the career building process” (Bridgstock, 2009).

Career Readiness is one element of employability development, and is key to developing students’ ability to gain highly skilled employment. Research suggests that where “career learning is situated within the students’ disciplinary context and combines with meaningful experience of the workplace there are considerable labour market benefits” (Taylor and Hooley, 2014). Career learning in tandem with work experience exposes students to new career ideas and broadens horizons, and contributes to the “recognition and development of other elements such as generic skills, emotional intelligence, reflection and self-confidence” (AGCAS, 2019). A recent review of research indicates that career learning within the curriculum is associated with increased self-efficacy, has a positive impact on retention and academic achievement, and develops entrepreneurial and networking behaviours and attitudes (Healey, M. 2020).

The Model

The Career Readiness model is based on the widely recognised DOTS framework for career learning, incorporating Decision-making, Opportunity Awareness, Transition Learning and Self-Awareness (Law and Watts, 1977), further developed by the SOAR model: Self, Opportunities, Aspirations, Results (Kumar, 2007). The value of this four-part model “lies in its simplicity, as it allows individuals to organise a great deal of the complexity of career development learning into a manageable framework” (Dacre Pool, 2007).

The four elements of Career Readiness are dynamically linked, with for instance individuals’ developing self-awareness leading to an ability to engage in more focussed career exploration, which in turn enables realistic and meaningful career decisions to be made. While set out as four distinct components, in reality individuals may engage with different elements concurrently, moving backwards and forwards as their career thinking develops, and “in the warp and weft of teaching and learning these separate aspects will be woven together and are capable of being combined in many permutations” (AGCAS, 2005).

In Practice

Career Readiness learning is “highly personal, applied and depend on reflective processes” and as such personally engaging methods are most appropriate, for instance, self-audits of career skills, role plays, problem-based group work and peer review of CVs and portfolios (Bridgstock, 2009). Such interactive student-centred techniques enable students to act, reflect, plan and personalise their learning, adapting it to their needs and aspirations. “Self, peer and tutor assessment, formative and constructive feedback … help to stretch students out of their comfort zones into a ‘safe risk zone’ where they can learn and grow” (Kumar, 2007).

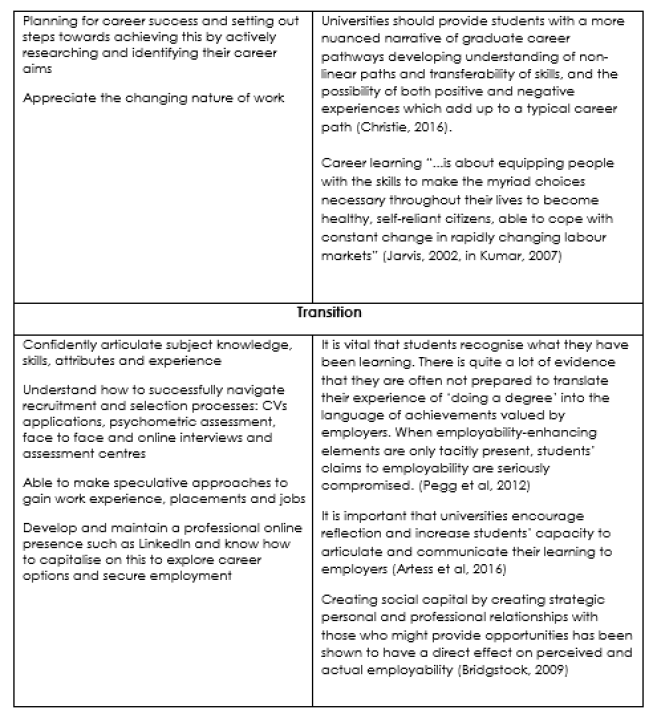

This is achieved through the four Career Readiness elements:

References

Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services AGCAS (2005) Careers Education Benchmark

Association of Graduate Careers Advisory Services AGCAS (2019) Curriculum Design Toolkit

Artess, Hooley and Mellors-Bourne (2016) Employability: A review of the Literature (HEA)

Bridgstock, R. (2009) The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: enhancing graduate employability through career management skills, Higher Education Research & Development

Christie, F. (2016) Uncertain transition: exploring the experience of recent graduates, Research report prepared for HECSU ,

Dacre Pool, L and Sewell, P., 2007. The key to employability: developing a practical model of graduate employability. Education & Training, 49(4), pp. 277-289.

Jackson, D. and Wilton,N. (2017) Career choice status among undergraduates and the influence of career management competencies and perceived employability, Journal of Education and Work

Kumar, A. (2007). Personal, academic and career development in higher education SOARing to success. London: Routledge

Law, B. & Watts, A. G. (1977). Schools, Careers and Community: A study of some approaches to careers education in schools. London, UK: Church Information Office (pp. 8-10).

Rust, C. & Froud, L. (2011). „Personal literacy‟: the vital, yet often overlooked, graduate attribute. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 2(1), 28 – 40.

Pegg, A., Waldock, J., Hendy-Isaac, S and Lawton, R (2012) Pedagogy for Employability (HEA)

Taylor, A.R. and Hooley, T. (2014) Evaluating the impact of career management skills module and internship programme within a university business school, British Journal of Guidance & Counselling