I have no reliable tip for the Kirkgate Handicap, which is run at 2:30 at Ripon on Thursday 8 June, and, since I know that’s the case, it’s probably sensible to avoid predictions for the General Election on the same day. Indeed, as regular readers of this blog will know, I was intending to source my online news for the last few weeks from the Wanganui Chronicle, so my own predictions are likely to be even less reliable than anyone else’s. However, even so-called seasoned and thoughtful observers like the widely-read Nate Silver of the fivethirtyeight.com website are currently coming up with articles like this one, which essentially boil down to ‘I’m sorry I haven’t a clue’, so you might, after all, be better sticking with the punt on the Kirgkate Handicap after all. The Emmy Award-winning American comedienne and author, Gilda Radner, whose own life was unpredictably cut short at the age of 42, was as keenly aware of unpredictability:“I wanted a perfect ending”, she wrote. “Now I’ve learned, the hard way, that some poems don’t rhyme, and some stories don’t have a clear beginning, middle, and end. Life is about not knowing, having to change, taking the moment and making the best of it, without knowing what’s going to happen next”.

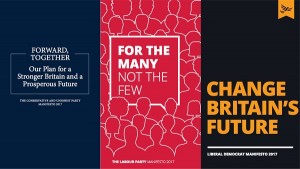

The election manifestoes offer starkly different visions for higher education, although they avoid – as perhaps manifestoes always do – some of the tough questions which follow from their headline propositions. The Liberal Democrats, still badly burned from their ill-fated 2010 pledge not to raise student tuition fees, say almost nothing about higher education. Labour’s signature pledge is to abolish student tuition fees. It’s a headline- and imagination-capturing pledge, albeit one with slightly curious implications. On the current pattern of participation in higher education, it would constitute a significant subsidy to the better off – though this has to be tensioned against the social good involved. Less obviously, it would almost certainly involve the re-introduction of student number caps. Until 2015, when the coalition government abolished the cap, government set a total number for the student places in the university system. This translated into a number for each university, albeit within tolerance limits. If there is to be public funding of student fees, there simply has to be a national cap – it is impossible to plan the public finances without a limit on numbers. At the time, the coalition government made much play of abolishing the cap, declaring that government should not be deciding whether individual students went to university – although of course the Chancellor of the Exchequer was never really the nation’s admissions-tutor-in-chief. The impact of removing the cap has been less to encourage larger numbers to go to university, but to redistribute places within the university system – some universities have grown rapidly and, because the A-level examination system sees to it that the number of young people in the system with given grades is fixed, others have shrunk. Against a background of sharp demographic decline – the number of eighteen-year-olds in the UK falls by 20% between 2012 and 2022 – the result has been sharper competition in a shrinking market. Labour’s proposal would essentially fix the size of the market and, given competing demands for public spending, would make funding for university teaching dependent once again on political decision-making: this was the mix which produced a serious crisis in university funding in the early 1980s. The consensus amongst policy commentators is that while Labour’s policy may be eye-catching, it does not answer tough questions about funding, widening participation or social justice.

The Conservative manifesto is sharply different, but also portends some very significant policy shifts. Put at its simplest, the manifesto suggests that the Conservatives look to be shifting their attention from higher to further education. They offer a far-reaching review of all ‘tertiary education funding’, without spelling out what this means; but, set against their proposals for a significant expansion of technical education and an extension of the skills base, the implication is a shift of policy priority away from higher and towards further education. The disappointing element in the manifesto, at least here, is that the relationship appears to be constructed as a zero-sum game rather than seeing further and higher education as intricately linked in the development of a highly-skilled economy and society. The Conservatives have reiterated a proposal from their Autumn Green Paper – widely criticised at the time – to require that universities take on the direct sponsorship of (it implies) secondary schools as a condition of being able to charge higher fees. Elsewhere – though not in the education section – the Conservative manifesto re-affirms the importance of universities to a post-Brexit research and development-led industrial strategy. All of this suggests a conception of universities as a whole which is tightly focused on the development of a high-skill, innovation-led economy. It might be described as a mercantilist vision of higher education – mercantilism being the view, dominant in the eighteenth century, that the goal of economic policy was to regulate a national economy in order to gather as much economic power within the country at the expense of rival powers. It is certainly at odds with the globalist internationalism which has underpinned higher education policy, and much university thinking, for the last twenty years or more.

These are sharply different policy prescriptions. Whatever the outcome, there will be some challenging changes in our operating environment for the University, and we will need to work hard with the new government to understand how best to respond to them. I’m not going to hazard any prediction on this, or the races at Ripon. But I will make one confident prediction: not mentioned in anyone’s manifesto, but the outcomes of the full trial of the Teaching Excellence Framework – itself a direct result of the 2015 election – will be out on 14 June, and a good part of my weekend was finalising statements of findings for each university.