I was recently team-teaching and my colleague was speaking to our students about how they should use the Module Learning Outcomes and Pass Descriptors to inform their work and used the phrase “allowing you to experience success”. There was a slight buzz of conversation in the room and I overheard a few students muttering ‘I didn’t know they could do that’ and (bearing in mind these are trainee teachers) ‘have you ever done that with your learners?’.

I found myself pondering what the experiences of our trainees must have been in the past to leave them surprised that assessors would be seeking to support their success. I recalled an article from The Florida Times Union which considers whether P.E. students should be graded on what they can do or what effort they make. A contributor noted: “You should not be graded on how fast you run a mile, the grading scheme should be based on the process, not the product.” (Amos in Florida Times Union, April 15th 2015). The context of this comment was a learner who, because they were unwell and therefore did not exceed their previous best speed, was down-graded from an A to a C.

This in turn made me think about NSS results: it’s well known that NSS scores for assessment and feedback are a concern for the H.E. sector, but do we have a good understanding of why they are low? Some research into the possible reasons was carried out for the HEA in 2010 (Crawford, Hagyard & Saunders) and amongst the key findings were “Preparing students to understand, receive and make the most of assessment feedback takes time” and “When informing students about the assessment requirements and submission dates, it helps to provide clear indications of when and how feedback will be provided as well as the roles and responsibilities of both staff and students“. But might it (also) be that students are actually less aware than we think of how marking is carried out? Or could it be that some assessors really do look for ways in which they have not met the pass criteria – or at least that some learners perceive this to be the case? Perhaps feedback itself isn’t the whole story.

I noted to plan a session with our trainee teachers where we will look at some grade descriptors and some samples of work and investigate how the trainees tackle assessment themselves, then explore whether they are all doing it the same way and proceed to discuss ways to ensure that learners are given the maximum possible credit for their efforts, without undermining the integrity of the assessment process.

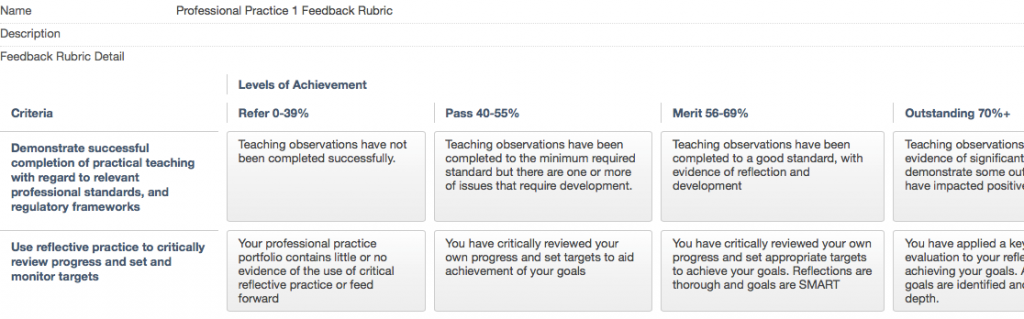

Later I had another thought: does the way in which grade descriptors and pass criteria are presented influence how learners and assessors perceive, understand and use them? It came to my attention that all the grading rubrics for modules I have taught for the last four years are laid out in four columns with the refer criteria on the left, then pass, merit and finally distinction on the right.

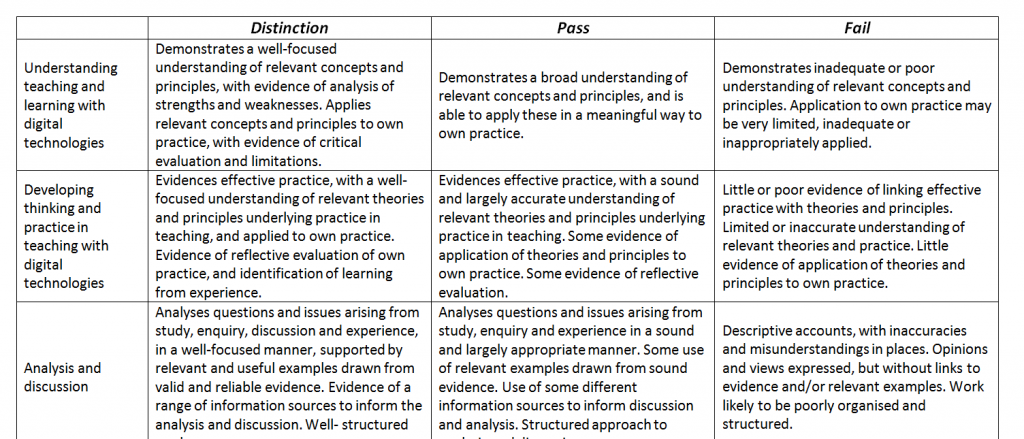

A quick scan of grading rubrics on a modest sample of Blackboard module sites revealed that almost all are set out in the same fashion, but in my external examining role I noticed that at another HEI all of their grading rubrics are laid out with the highest marks on the left and the refer marks far right.

As we read from left to right, does this influence the way that learners approach their work? Does it influence the way in which assessors mark work? Might it encourage ‘marking to fail’, albeit completely inadvertently and / or subconsciously. These are questions I certainly can’t answer at this time, but I would like to investigate.

A starting point for research is often a literature review, but interestingly, when I performed a search for literature on this topic, almost nothing was apparent. Instead literature was readily found on appealing marks which students perceived ‘unfair’ and there is much media coverage of assessors protesting that they are being encouraged to award marks which they do not feel are merited in order to maintain student numbers – “… recent reforms, which encourage universities to … expand their intake, … In 2014, record numbers of students left university with a first-class degree, prompting claims that grades are being inflated. The number of firsts has more than doubled in the decade since 2004,…“. (Guardian, May 18th 2015: https://goo.gl/ruWZv0 )

There is a certain irony that, in a profession where encouraging learners, and planning to afford all learners maximum opportunity to experience success, because “By allowing learners to experience success throughout multiple levels of learning, they will develop a positive self-perception of their ability.” (Fazioli, M. P., 2009), the new entrants to the profession appear unaware of the concept of ‘marking to pass’ and instead – apparently – expect that they themselves will be ‘marked to fail’.

Having sparked my interest I am now planning to research approaches to marking and assessment.

Dave Darwent is a Senior Lecturer: E-Learning Technologist at Sheffield Institute of Education

Leave a Reply