Four thousand students at Sheffield Hallam are eligible to wear the International Student wristband. These identity markers draw institutional distinctions surrounding fees, immigrations rules, police registration and visas. But wearing the wristband can trigger images of students who lack criticality, are passive, plagiarize, and follow other deficient learning habits.

Lecturers and students do well to challenge the essentialist pictures behind these images. But rather than fuss about the details of particular international stereotypes, what needs to be contested is the thought process behind their production.

Sheffield Hallam has a student body that is super diverse. If we tried to make the wristband represent each individual more precisely, the categories would become endlessly multiple. Indeed, UK students may call on identities from the four nations of the kingdom, or a particular region or community. Our students are working through a range of identities which are unclear, fuzzy, and complex. In this, we are all in the same multiple boat.

The Home / International distinction blocks us from seeing our students as individuals. And if we are blocked from seeing the complex individual, we can’t see the potential. We may only see a threat to what we are familiar with instead of an opportunity to learn and enable learning.

Personal stories are a good way of removing these blocks. If you haven’t got a story, a picture will do. Sempe’s cartoon, ‘nothing is simple’ picks out a moment which may be part of many complex narratives. These are fun to explore and, as narratives, lead to chains of other narratives. It’s a different way in than a blunt question about a contested border (like the one in the cartoon).

I don’t want to romanticize diversity and ignore practicalities. After all, students need to meet their learning outcomes. My feeling is that understanding students as starting from a galaxy of current points but going through a common process of learning helps when I run sessions on academic language. It helps me to acknowledge the rich, lived academic experiences that the students are moving through and to help them navigate for themselves. And it helps me to lift proficient speakers of English out of the idea that they won’t have to do the necessary mental acrobatics to produce the precise and abstract language of their university assessments.

A way of opening this up is to think of academic language as a foreign language that we all need to learn. To do so, we need models of language and descriptions of academic texts which empower all students as they go through the common process. The whole student body needs to struggle to covert their linguistic and cultural capital into academic capital.

Removing obstacles to thinking, like removing the ‘International’ wristband from the classroom, helps to open up new meaning making. I’ll suggest one concrete activity to help with the process of freeing up our sense of International students which also relates to abstraction in academic writing.

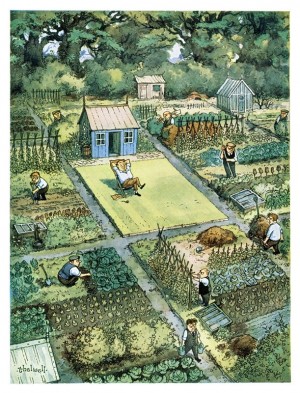

In the classroom, in addition to opening up discussion about ourselves and others, a simple cartoon is an accessible way to get the process of precise and abstract meaning-making started. The Punch cartoon below by Norman Thelwel (1954) can be used to prompt students to co-construct meanings that move towards a shared understanding rather than difference. The discussion prompts are simple: What happened before? What will happen next? What does this mean? After a period of talk, getting the students to write down a caption will probably stop their meaning making in its tracks and create an understanding that they stick with (tell them that it’s not usually a good idea to bring your thought processes to a halt like this). From there, students can contrast Thelwel’s view life with that shown in Sempé picture – a powerful resource for finding common understandings across groups.

But how about the language of the university? The cartoon activity can be developed do introduce notions of abstraction. A linguist might draw attention to another process: nominalization and abstraction. Look how the grammar changes in in the following captions.

That man is resting but the others are gardening in the afternoon.

The man’s garden lets him rest while the others work.

Restful gardens and hard work gardens…

The garden of happiness and satisfaction…

Contentment.

Making abstractions like this is a process of nominalisation. It is as difficult for any student as it is important in academic writing. Big noun groups are a feature of academic text that makes readings difficult to comprehend (the italicized words are a noun group). Of course, big noun phrases are just one example of the grammatical challenges of academic discourse. The challenge increases when you move to stretches of language that are longer than a sentence. But drawing attention to these features are an important way of helping all students on their academic journey.

In order to remove the ‘International student’ wristband from our thinking and to move to the common ground of the complex grammatical challenge of academic meaning making, we need a model of student which is open and a model of language which acknowledges of collective struggle with academic meaning making.

John Wrigglesworth teaches academic writing in the TESOL Centre.

The TESOL Centre is happy to engage with all students and staff regarding academic discourse.

Leave a Reply