Doreen Massey died recently. ‘Doreen who’ I hear most of you asking? She was a feminist, a geographer and a political activist who worked at the Open University (http://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/mar/27/doreen-massey-obituary). Like other cultural icons we’ve lost recently (David Bowie, Prince, Victoria Wood, Muhammad Ali) Doreen Massey’s death feels significant. Along with a few others (Henri Lefebvre, Edward Soja, Yi-Fu Tuan) she had an incredible influence on how we see and think about space and place. Her work has meant a lot to me over the years in my teaching, research and thinking and I wanted to use this blog not just as a little homage to Doreen but as an opportunity to consider the vital role space and place have in higher education, in connecting us to others, and in shaping who we are.

Doreen Massey viewed space as ‘a pincushion of a million stories: if you stop at any point in that walk there will be a house with a story’. Over time, our stories deepen as they intersect with others’ stories, bringing together many different spaces, places, people, things, memories and emotions. Also over time, our stories evolve and change as a result of these spatial intersections. Having taught for many years, I feel secure in saying it’s probably impossible to go through any course of higher education without being changed, and that much of what we do as university educators is about creating spaces which foster positive changes for our students.

Belonging – that feeling of being ‘in’ or ‘out of place’ – has always been crucial in a University like Sheffield Hallam. The main reason I came to work here in 2008 was because of its commitment to widening participation. But it’s only when you drill down that you get a real inkling into how profound the relationship is between belonging, identity and place. One example of this comes from an undergraduate module I teach, Experiencing Spaces Embodying Education, in which students use an autoethnographic approach to write about a critical incident that occurred in a particular place in their educational lives. Every year I am touched by the stories students tell. This year, one student wrote about a harrowing school visit to Auschwitz-Birkenau while another about gendered bullying in school changing rooms. Reading their work reminds me again that each person’s spatial story is unique and significant.

Like Massey, I think it’s the little things we do to make space matter to us that really count. I’m struck at the beginning of each new academic year with how new students choose where to sit and then usually continue to sit in that particular space for the rest of the module. This is about finding, holding onto and orientating themselves as the temporary owners of that particular spot. Feeling comfortable where you are, in the sense of having a temporary place in that bigger space, is important to learning. Children do it in school when they position objects on their desks to create a little personal space to work, think and probably daydream within.

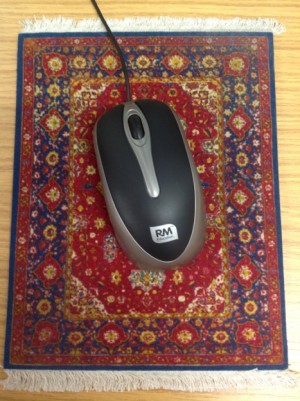

Everyday practices of belonging are central to my current British Academy/ Leverhulme funded research project, in which I’m using creative methodologies to explore how students and staff inhabit and claim space in a new university building. The small tactics and practices for personalising and ‘borrowing’ space, such as putting things from home on your desk, having your own mug or cup, a plant, or maybe a photo, speak to the modest but fundamentally important ‘groundwork’ that we all in some way do to mark the fact that ‘I am here’ in this space and I matter.

These ‘local’ spatial practices are also part of a broader ‘politics of space’ across the higher education landscape. Indeed, the new Charles Street building, which houses the Sheffield Institute of Education, takes its place in Sheffield (and nationally) as a ‘flagship’ building embodying both a certain vision and a set of values about education. The Charles Street building has some wonderful classrooms, technology, and open study spaces. It has a nice café, too. But it’s on Corin Mellor’s bridge with rivets made from ‘good and proper’ steel, in the rusting skin of the roof, and on the terraces which overlook the city that the building’s ‘feel’ – and intention to connect past, present and future – makes itself apparent. In these spaces, the building is developing a story which ties the new into the industrial and civic past of the city. I’d invite you to go and stand on the building’s roof terrace and experience space as a kind of time travel!

Doreen Massey’s work continues to make me ask: who is this particular space we are in here and now for? Whose bodies are here and whose are not? Why do some feel they ‘belong’ while others are ‘excluded’? What has to happen to ensure that all can belong, irrespective of starting place? And who is going to make that happen? Ultimately, this is why space matters to me – it leads into some fundamental questions about who we are as educationalists, how we design pedagogic spaces that can truly include all, and how we can try to embody the values we believe in as educators in all the spaces and places we inhabit.

Dr Carol Taylor is Reader in Higher Education in the Sheffield Institute of Education http://www4.shu.ac.uk/mediacentre/carol-taylor

Email: C.A.Taylor@shu.ac.uk

Leave a Reply