In the coming months we will see record levels of youth unemployment in the United Kingdom – levels higher than the periods following the 2008 financial crises or the 1980s recession. We know that unemployment has scarring effects which can last lifetimes – and the longer the period or periods of unemployment the more significant these are on both lifetime income and wellbeing. The long-term costs of not urgently addressing this coming crisis far outweigh the costs of properly funding a response now.

The National Lottery Community Fund’s £108 million programme was a response to the youth unemployment crisis which followed the financial crisis. From 2014-2018 Talent Match supported over 25,000 young people in 21 parts of England – from London to Newcastle and from Hull to Cornwall. £108 million sounds a lot of money but over 5 years and 25,000 young people it works at around £4,000 per person supported – an amount less than previous employment initiatives.

The 21 local voluntary sector partnerships which delivered Talent Match focused their support on those young people facing the greatest barriers in securing employment. The barriers were wide-ranging and many young people faced multiple barriers: from the legacy of adverse childhood experiences, homelessness, substance misuse and addiction, disability, low levels mental health, limited or no prior employment experience, to no or low qualifications. But what was also evident was that most of the 25,000 young people had individual career and life aspirations and they had talents.

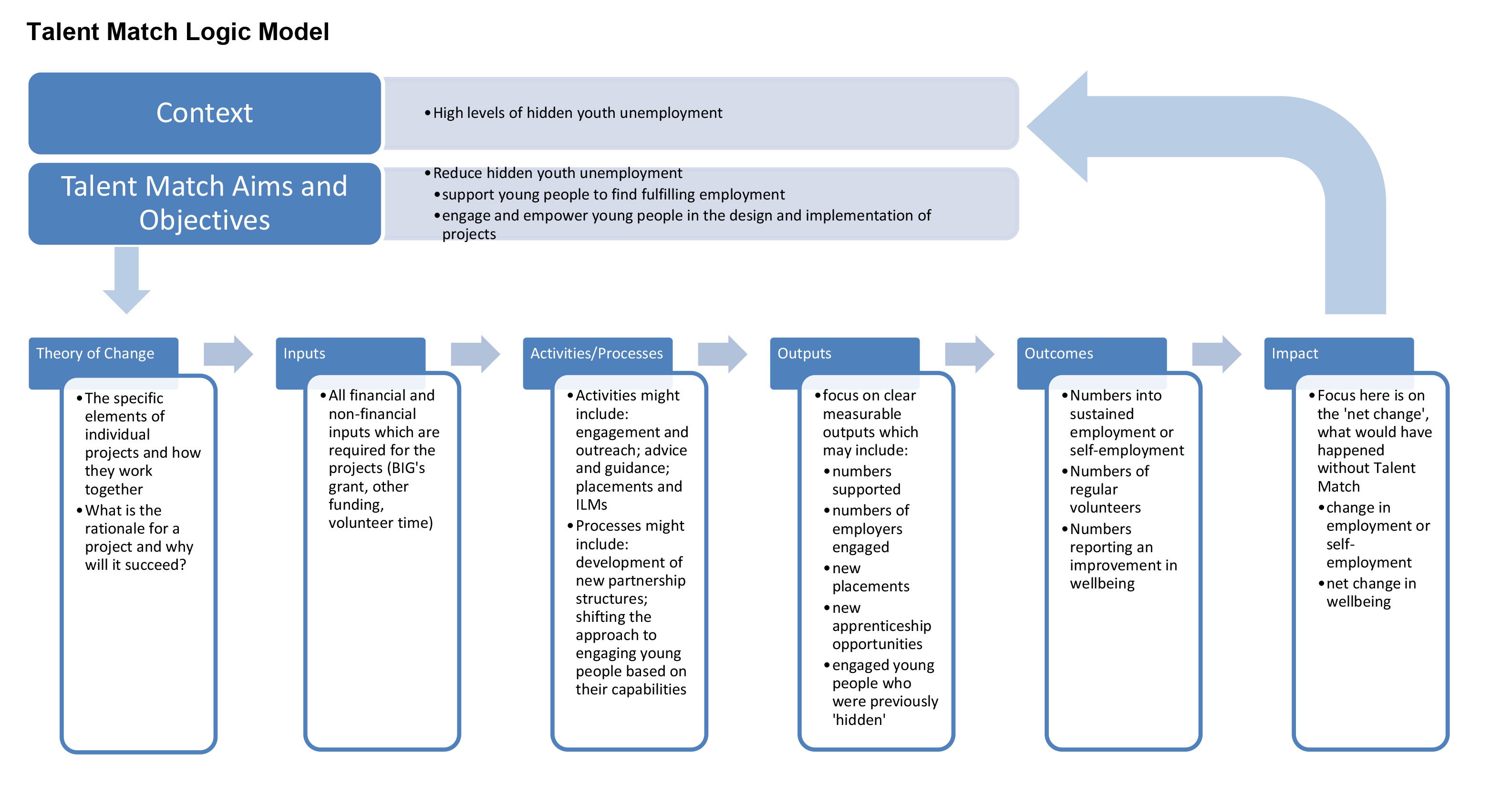

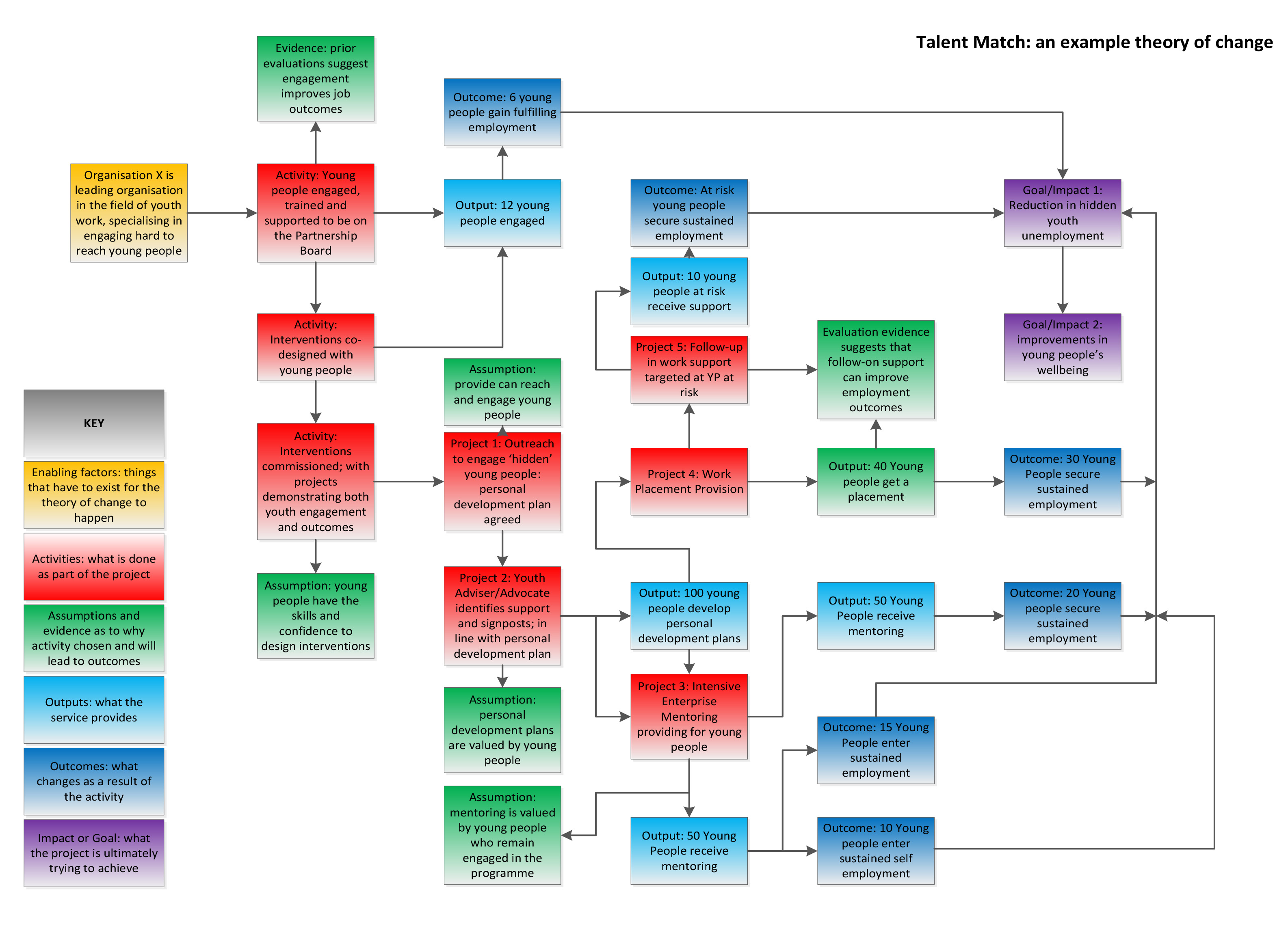

Talent Match was a radical experiment in youth employment policy. Rather than generalise as to the barriers young people faced and offer a one size fits all response, the programme took an approach which was focused on the needs, talents and aspirations of each individual young person. How did it do this? It started by asking young people what they wanted; whether in the design of the programme by the National Lottery Community Fund or by the 21 partnerships. The partnerships then engaged young people in the delivery of the programme: whether in understanding barriers, ensuring employers consulted young people or developing young people as peer mentors.

Here are some of the key findings from the evaluation of Talent Match which is published at the same time as this blog:

- A total of 25,885 young people were supported by Talent Match. Of these, 11,940 (46 per cent) secured some form of job, including 4,479 (17 per cent) who secured sustained employment or self-employment.

- Talent Match participants moving into work reported high levels of job satisfaction.

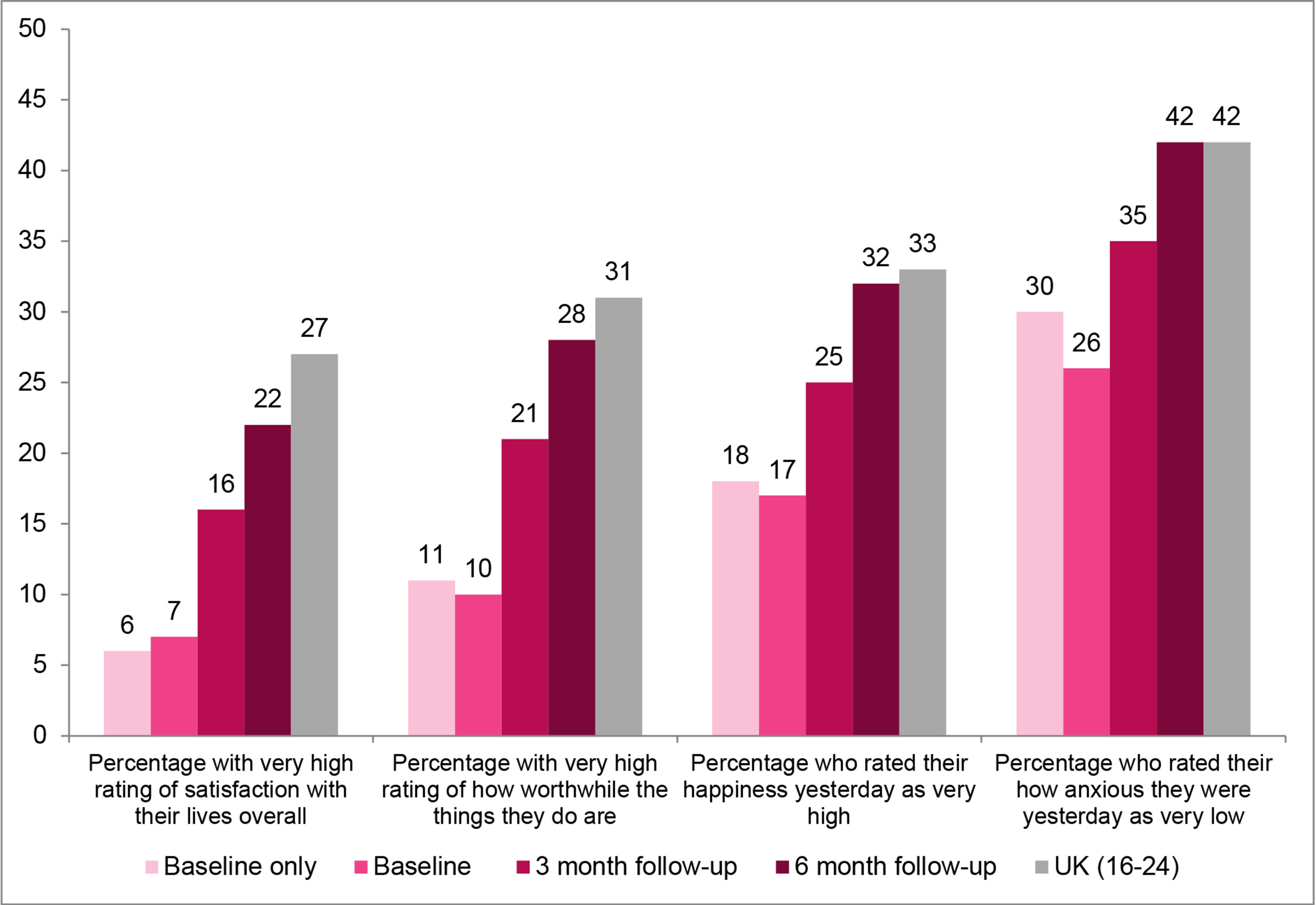

- Talent Match helped support participants to improve their wellbeing: 70 per cent of those who gained a job reported improved life satisfaction; and 60 per cent for those who did not gain a job.

- At least £3.08 of public value has been generated for every £1 spent on Talent Match programme delivery. This means that there is a positive social benefit associated with Talent Match.

- Lead voluntary and community sector (VCS) partner organisations effectively engaged other organisations from across sectors, including employers.

- The involvement of young people was the key feature of programme innovation and lessons on successful co-production can be drawn from Talent Match for future practice.

But Talent Match alone is not a panacea: young people, especially those facing multiple barriers (including low skills, limited employment experience, homelessness and low levels of wellbeing) will continue to need support regardless of the state of the national economy and the level of unemployment. They will need support in entering and in sustaining employment. Payment-by-results approaches to delivering employment programmes often mean there can be few incentives for providers to help these groups.

There are nearly seven million 16-24 year olds in the UK; around 1 in 10 of the national population. The last recession led to youth unemployment peaking at 1.4 million in 2011. During the period of the great recession (2008-2012) perhaps double that number experienced unemployment at some point. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the national economy is already greater than the financial crisis. What can be done to prevent between a third and a half of today’s 16-24 year olds experiencing unemployment?

As evaluators with long standing experience of employment programmes and drawing on the experience of Talent Match we believe that the following are now needed:

- Youth involvement: the crisis faced by young people today differs markedly from the challenges they faced in previous periods of high unemployment. A different approach is required which recognises that work first solutions alone are not enough. Engagement with the diversity of young people in the design and delivery of the response is essential; tomorrow’s economy and the nature of work is likely to look very different from those of the past.

- Person-centred approaches and key working: the value of high-quality relationships between participant and employment support provider were found to be crucial to initial and ongoing engagement. This was especially the case for young people furthest from the labour market.

- Partnership and local employment support ecosystems: Devolution may offer the opportunity to build local employment support ecosystems. These can overcome some of the challenges of short-lived programmes interventions which have constrained employment support for a long time.

- Support for those who need most help: at a time of huge unemployment there is an obvious tendency to focus on those closest to getting jobs. A risk of this approach is that those furthest from work, facing multiple barriers, are not given any priority. This is wrong and runs the risk of permanently excluding a group from employment and opportunities to live fulfilling lives. The response should start with the offer of a job guarantee to all those young people out of work for more than six months or who face multiple barriers in obtaining and securing employment.

- Scale of investment required: The last major national government programmes were the New Deal for Young People which ran from 1998-2003 and cost £1.5billion and the Future Jobs Fund which ran from 2009-2011 and cost £1billion. Both had significant effects proportionate to those of Talent Match. We would advocate the development of a programme of similar ambition but designed to the challenges of today’s economy. Any new programme should ring fence at least a quarter of its budget to support those furthest from the labour market. Whilst the newly launched Youth Futures Foundation is an important start, its £90 million endowment may simply not be big enough for the challenges we face.

Finally, addressing youth unemployment cannot be left to project-based funding models. It requires investment in organisations and partnerships at a local level committed to changing the fortunes of nearly 7 million young people in the UK.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely grateful to all those who have helped in the course of the evaluation. We are particularly grateful to the staff, young people and board members of the 21 Talent Match partnerships who have given their time freely to support the evaluation. A mention should be made of partnership leads and those involved in setting up the Common Data Framework (CDF). We trust that in time the considerable benefits of the CDF will be seen in terms of contributing to a robust evidence base on which to design future policies and programmes.

A wide range of staff and committee members at The National Lottery Community Fund have helped, supported and advised upon the evaluation. Their time has been invaluable. We are particularly grateful to Jolanta Astle, Sarah Cheshire, James Godsal, Scott Hignett, Scott Hyland and Roger Winhall. We are also grateful to former National Lottery Community Fund colleagues Matt Poole, Linzi Cooke and Scott Greenhalgh who provided invaluable assistance at the start of the Talent Match Evaluation.

Lastly, we would like to thank the evaluation team at Sheffield Hallam University, the University of Birmingham, the University of Warwick and Cambridge Economic Associates: Duncan Adam, Gaby Atfield, Dr Sally-Anne Barnes, Nadia Bashir, Dr Richard Crisp, Dr Chris Damm, Dr Maria de Hoyos, Dr Will Eadson, Professor Del Roy Fletcher, Dr Tony Gore, Professor Anne Green, David Leather, Elizabeth Sanderson, Emma Smith, Louise South, Professor Pete Tyler, Sarah Ward and Ian Wilson. We would also like to thank our former colleague Ryan Powell who supported the original evaluation design and engagement with all the partnerships.

Peter Wells (Evaluation Director) and Sarah Pearson (Evaluation Project Manager)