Engaging the Silent Majority

Dr David Smith – HE Bioscience Teacher of the Year 2019 and National Teaching Fellow

Dr David Smith – HE Bioscience Teacher of the Year 2019 and National Teaching Fellow

How can you ensure all students in a teaching session have the opportunity to engage, be involved and interact?

This is the question that I wanted to address when I set out to understand why students choose to sit in a given location within the lecture theatre.

Learning Spaces Research

My case study presented to the Royal Society of Biology was centred around a paper I published alongside Dr Mel Lacey and my student at the time Angela Hoara. It was entitled “Who goes where? The importance of peer groups on attainment and the student use of the lecture theatre teaching space“. The research determined not only where the students were sitting but why they chose that location. This video below explains the core concept and findings of this work.

[Resources created by Sam Smith and Claire Hannah, Learning Technologists in the directorate of Learning Enhancement and Academic Development at Sheffield Hallam University. Read more]

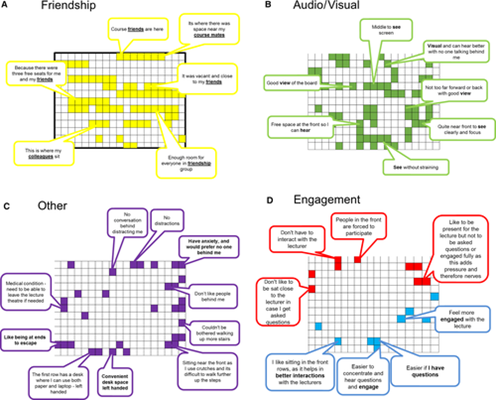

Students were asked a simple question, “Why are you sitting in the location you are today?”. Responses were coded and mapped back onto the lecture theatre, alongside the outcomes of assessment tasks. The study was performed on a mixed cohort of ~300 first and second-year students taking Bioscience related degrees. A range of social and environmental themes emerged from the dataset around seating choice and are summarised below:

- Friendship: Students would sit in rows with peers on the same course. For example, we would have three or four Biomedical Scientists from one tutor group sitting on the same row as a group of Human Biology students. “we as the ex‐foundation year all sit together because we are friends”.

- Audio/visual: The ability to see and hear was a major driving factor for seating choice. However, these choices were subjective with those at front reporting that they were there to see and hear better, which was precisely the same reason as those in the middle and the back.

- Engagement: A students willingness to engage with the lecturer determined if they sat at the front or the back of the room. Those at the front want to engage directly with the tutor, whereas those at the back do not. This pattern correlated with the tutor perception that high performing students sit at the front, and would indicate that staff relate overt engagement with achievement. “I feel more engaged with the lecturer.”

- Anxiety, nerves and lone working: Student comments around nerves and anxiety did show clustering to specific areas of the lecture theatre driving students to sit at the edge of the room. Students report doing this so that they could “escape”, “feel safe” and “avoid answering questions directly”.

Friendship groups get similar marks, but seat location does not matter

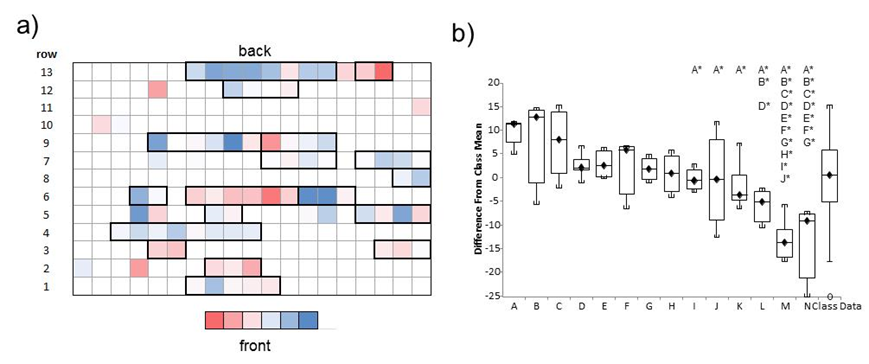

When we plotted the attainment of the students in either an individual essay or a problem-solving task, no clear pattern between location and grade was seen. Students sat at the back were equally likely to get the same mark as students sat at the front. However, clusters of similar marks could be seen which correlated with friendship groups. The image below shows the individual mark difference from the class mean on a heat scale with blue performing better and red performing worse. Looking at rows 6, 9 and 13, groups who scored above the mean are sat next to groups who scored below. These clusters of similar marks correlated with courses and self-identified friendship groups. This would indicate that these students are working together and obtaining similar scores on problem-solving tasks. What was particularly worrying was the lone students at the edge who tended to score below the class mean.

Change the dynamics during peer-assisted learning

One of the most substantial reasons for seating choice in the learning space study was to be sat with friends. Interaction with peers can positively influence overall academic development, knowledge acquisition, problem-solving skills, and self-esteem (Kuh et al. 2006). Kram and Isabella (1985) identified within the workplace, and by extrapolation in the learning environment, three types of peers groups:

- Information peers are acquaintances with whom communication is focused on the exchange of information. (someone you work with to complete a task)

- A collegial peer is considered to be a co-worker who also acts as a workplace-based friend (someone you talk within the teaching space but not outside the teaching space)

- A special peer is considered to be a co-worker who also is a friend outside the workplace. (someone you talk within the teaching space and outside the teaching space)

Peer learning sets out that students interact with each other to obtain educational goals. During large group teaching, think-pair-sharing activities are used extensively and are championed in lecturing handbooks as an active learning tool. Students are given a question or problem by the tutor and asked to share the answers or solution with classmates. Given the location choice of the students, these conversations are likely to be with a friend at a similar level of attainment. There is then the risk that misunderstanding or self‐validation of mistaken ideas can occur and be propagated through the group. To prevent this and facilitate a broader sharing of knowledge the way think-pair-sharing was conducted within large groups was changed. Instead of talking with the person next to them, students were instructed to swap written work or speak with people in front or behind them. This would break students out of their collegial and special peer groups and form transient interactions with information peers. The written format meant that for the more nervous or lone student conversations with people they didn’t know would be limited. Groups of differing abilities are then able to exchange knowledge and ideas any misunderstandings can be identified and addressed.

Interacting with the silent majority

It is essential to student learning, wellbeing and equality that all have a channel through which they can interact with the lecturer. Many students identified as being anxious and chose their seat to prevent people sitting behind them, or sat at the sides to better manage their anxiety. How then do you engage with these students, who have selected locations specifically not to interact with the tutor?

The solution to this problem was to use open text response systems during the lecture. Anonymous responses from internet-enabled devices allow students to ask questions without the fear of being called out in front of their peers. There are a variety of open text response systems (Padlet, Socrative, TurningPoint, Google Forms, etc.) that can be used and most of them are free for educational use. I tend to opt for systems that do not require a login so that identifiable student information is not given to third parties. It is also essential that the system works well on mobile phones.

In practice, pause points are introduced into the lecture to allow interactions. Students are directed to the text response system by URLs or QR codes, either a problem is set directly by the tutor or the student are have the opportunity to ask questions of their own. The questions act to consolidate the knowledge at that point or to apply what has been taught. A pause point was timed to take place every 20 min, and around 10 min of lecture time was given over to the tasks. For example, here are three pause point questions taken from a lecture around genomic editing. Each item builds on the last moving from knowledge recall to application:

- Outline the molecular basis of CRISPR.

- How can CRISPR be used to edit a gene in cell culture?

- Design an experiment to create a cellular model of a disease of your choice.

The tutor’s role is to monitor the text responses and give guidance into areas that could be expanded, as well as correcting any misunderstandings that arose. This intervention sets up a two-way dialogue, allowing the level of understanding and any misconceptions to be addressed. Removing the need to speak openly, allows the anxious or lone students to have their voice heard and the opportunity to ask or answer questions they wouldn’t usually contemplate.

Beware the Trolls! Open text response systems are open to misuse. In past experience, when the responses have been displayed on a screen for all to see, “silliness” has occurred. To keep the use of the systems on task, ground rules can be set with students, and the reasons for using the response systems explained. Moderation of posts or a second screen that only the lecture could see was used to prevent inappropriate material being shown. These approaches made sure that technology was used in a beneficial way that aided everyone’s learning.

Reflections

I entered into the lecture theatre study with preconceptions about my students and how they engage. Uncovering that anxiety and nerves were forcing students to the edges of the room was a real driving factor in the introduction of the interventions. Anonymous communication has led to a richer learning experience for all and has helped me discover where gaps in student knowledge occur. Drawing the study together for the RSB was an uplifting experience. Hearing from my peers and students on how the ideas around student interaction have impacted on the learning experience, and how it has been used to increase inclusion has been fantastic.

Acknowledgements

I must thank, Mel Lacey for being my collaborator in our pedagogical research and developing the practice. Mel Green, for all her advice and input into my blog. My peer group in the Bioscience and Chemistry department at Sheffield Hallam University, Biochemistry Society and Society of Experimental Biology for helping me develop the practice. Sam Smith and Claire Hannah for their AV wizardry. My wife Rachel, who gives me the time-space and inspiration to keep trying out new ideas. But, I especially want to thank my students for allowing me to try out the ideas and playing along.