Apostasy and Hate Crime

People who leave a coercive religious group face a huge struggle, thousands of young people have been brought up in religious traditions where ‘coming out’ as not believing can lead to threats, shunning, psychological abuse, discrimination and physical harm.

Deciding to leave a religion can often mean rejection from your family and community, with little understanding of where to turn next. ‘Apostates’ as these people are sometimes called, may end up homeless, isolated, and at risk of profound mental health issues.

Apostasy has not been comprehensively studied and statistics on the experiences of people leaving religion are hard to find. A survey commissioned by apostasy support group Faith to Faithless showed that that nearly half experience significant mental health issues, and that two thirds experience physical harm or threats.

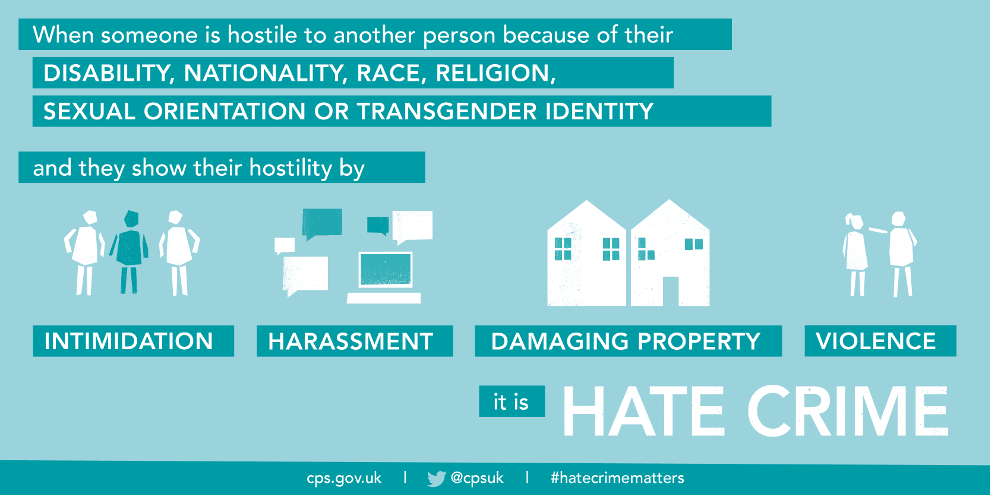

Freedom of religion or belief in the UK is protected by the Human Rights Act, Article 9, which includes the right to change your religion or beliefs. Religion or belief is a monitored strand under hate crime law, and so violence, intimidation or harassment due to apostasy would be considered as hate crime.

The Government has confirmed that currently no data is collected on anti-apostasy hate crime. Greater awareness of the issues faced by apostates is needed by public services, and recently Faith to Faithless carried out their apostasy awareness training with the Metropolitan Police Force to better enable the police to identify and respond to these issues.

Apostasy is also linked to questions around freedom of speech, as the act of questioning faith or leaving religion altogether is considered an act of blasphemy by some. A 2017 report found that 71 countries have blasphemy laws including Scotland, N Ireland, and Rep of Ireland, and even though often not actively used can still cause harm by their international influence. Countries defending convictions under their blasphemy laws will cite the existence of such laws in European countries as justification. Many countries also have laws against apostasy, which in twelve states incurs the death penalty.

Rep of Ireland recently voted to remove its blasphemy laws from the constitution, which is an important step in protecting the rights of ex-religious people. An article by Rights Info explains that engaging with these debates can highlight apostasy and blasphemy as “real issues affecting real people.” However, a legal framework protecting the right to leave religion may not be enough, and more work is needed to create dialogue and change societal attitudes.

Fiyaz Mughal, founder of Faith Matters and TellMama co-wrote a book ‘Leaving Faith Behind’ with Aliyah Saleem an ex-Muslim and co- founder of Faith to Faithless. The book contains the stories of five ex-Muslims, and their experiences of leaving faith, including two anonymous accounts from women, exploring the additional difficulties faced by women who leave their faith.

Fiyaz Mughal, founder of Faith Matters and TellMama co-wrote a book ‘Leaving Faith Behind’ with Aliyah Saleem an ex-Muslim and co- founder of Faith to Faithless. The book contains the stories of five ex-Muslims, and their experiences of leaving faith, including two anonymous accounts from women, exploring the additional difficulties faced by women who leave their faith.

Mughal argues that faith communities are damaged by repressing dissent and refusing debate. By giving a platform to marginalised voices, the book hopes to prompt “wider discussions about how faith communities and those who reject faith can listen to each other’s experiences with some empathy.”

Faith to Faithless will be delivering their apostasy awareness training to key stakeholders at Sheffield Hallam as part of the ‘Standing Together Against Hate’ project.

Any student apostates looking for supportive community and events can contact the Humanist Students society, or access pastoral support from the humanist advisor via the Multi-faith Centre by emailing chaplaincy@shu.ac.uk