Jenny Kurobasa is Senior Lecturer in Secondary Education in the Sheffield Institute of Education. Jenny works closely with mentors in schools. This blogpost aims to develop a conversation around the the key ideas of effective teaching and developing quality of teaching, and how this is related to the role of the mentor.

Jenny Kurobasa is Senior Lecturer in Secondary Education in the Sheffield Institute of Education. Jenny works closely with mentors in schools. This blogpost aims to develop a conversation around the the key ideas of effective teaching and developing quality of teaching, and how this is related to the role of the mentor.

The role of mentors in developing effective teaching

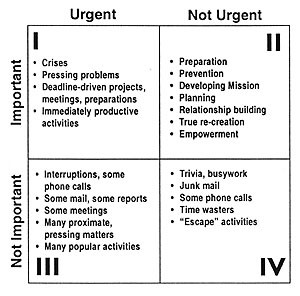

It is clear that mentors play a critical role in supporting mentees to develop into effective and reflective practitioners. In week 4 of the SHOOC we are looking at how the mentor supports and guides mentees to set high standards, and inspire, motivate and challenge learners: essentially, to understand what effective teaching is and be accountable for the achievement of learners. It is becoming increasingly recognised, that the benefits of high

quality mentoring can ensure a successful and positive transition for the beginning teacher into teaching and continue to make a substantial contribution to their professional development through their careers. It is also worth considering that the benefits can be just as far reaching for the mentor, school or college setting, and ultimately learner outcomes.

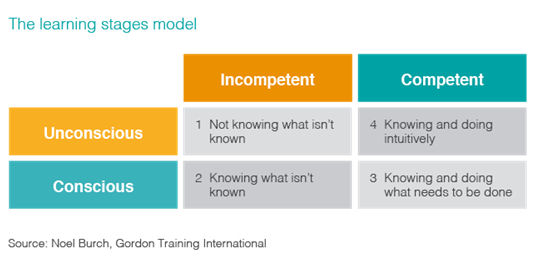

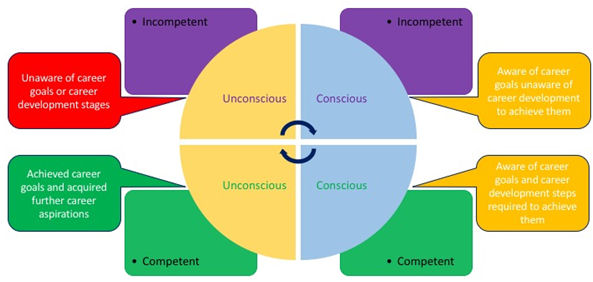

Beginning teachers are concerned with the understanding of the ‘act’ of teaching. How and where to stand in the classroom, learner entrance and exit, voice and pitch, controlling the class etc. Although, crucially important for preparing for constructive learning to take place, the trainee may not be fully understanding of why or what they are doing it for. This is not surprising because classrooms themselves are complex and dynamic environments and for the novice this can be overwhelming. The mentor, as an experienced teacher, is able to ‘think’ and consider learner progress and intuitively identify learning in a lesson because they are ‘unconsciously competent’ in managing the classroom environment. There is an interesting piece of related research to read. ‘Learning to See in Classrooms: what are student teachers learning about teaching and learning while learning to teach in schools.’ (Edwards and Protheroe, 2003)

Given that our aim is to develop the understanding and skill of mentees in becoming effective teachers, it is therefore essential to understand what effective teaching is and the role mentors play in impacting on this. A definition of effective teaching is that which leads to improved student achievement using outcomes that matter to their future success. (Sutton Trust 2014), Essentially, the most effective teaching is that which enables the most effective learning. The Sutton Trust report outlined six key components to assessing effective teaching:

1. (Pedagogical) Content knowledge (Strong evidence of impact on student outcomes)

2. Quality of instruction (Strong evidence of impact on student outcomes)

3. Classroom climate (Moderate evidence of impact on student outcomes)

4. Classroom management (Moderate evidence of impact on student outcomes)

5. Teacher beliefs (Some evidence of impact on student outcomes)

6. Professional behaviours (Some evidence of impact on student outcomes)

What can the mentor contribute?

A mentor is an experienced and expert teacher who takes on the additional role of supporting and developing colleagues. At different times the mentor is a:

- coach who provides a model of effective teaching and sharing practice.

- critical friend who observes the trainee teach and offers encouragement to develop expertise.

- trainer in subject knowledge and pedagogy.

- assessor for the Teachers’ Standards

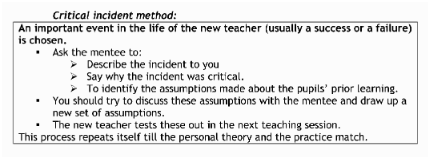

The successful mentor/mentee relationship is collaborative and mutually active. Both parties have a responsibility to explore, define and resolve mentoring issues. Mentors draw upon a wide range of relevant experiences, strategies and techniques from other aspects of their work. The mentor is not there to provide ‘the answers’, but to guide the mentee towards ‘the answer’ that is right for them. You do not have to have all the answers either; posing questions which can be resolved by working and learning together is far more important:

‘Asking a question is the simplest way of focusing thinking. Asking the right question may be the mostimportant part of thinking’ (Edward de Bono).

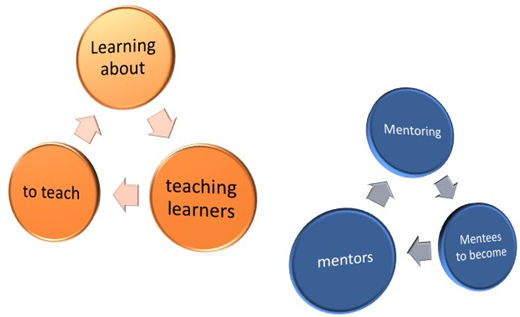

Sometimes during the relationship the mentor may be a ‘model’ to the mentee: giving direct support usually at the beginning of a training or learning activity when

understanding of the teaching pedagogy is limited or unpractised. The mentor may be a ‘guide’ to the mentee: developing the mentee’s understanding and confidence and then the mentor may be a ‘critical friend’: extending, enhancing and consolidating practice promoting independent thinking. However, it is not a master class. Mentoring is a ‘complex range of training activities and this is what makes for a complex relationship’. (Wright, 2012). Tomlinson’s (1996) model of mentoring assistance is useful here.

Understanding the journey that a novice takes

An examination of research literature on the process of learning to teach confirms the common sense observation that trainees typically go through a number of distinct stages of development, each with its own focal concerns. It is crucial to understand and part of getting to know and building a positive working relationship with your mentee. There are many theoretical interpretations of these stages. Maynard and Furlong (1993), ‘Common stages of student learning’ gives insight into how the mentee may respond to the learning activities through the training journey. This knowledge and awareness of the mentee journey is useful for the mentor to appropriately assist and ‘pitch’ the learning activity.

However, the development of any one mentee is more complex than a simple stage model implies; they will develop at their own rate and will need to revisit issues because they have forgotten them or wish to relearn them in a different context or at a deeper level. Therefore stages of mentoring should be considered flexibly and with sensitivity: cumulative rather than discrete. As mentees develop, mentors will need to employ more and more strategies.

Further Reading

Dudley, P (2011) Lesson Study: what it is, how and why it works and who is using it, www.teachingexpertise.com

Edwards, A., & Protheroe, L. (2003). Learning to see in classrooms: What are student teachers learning about teaching and learning while learning to teach in schools?. British educational research journal, 29(2), 227-242. (available here)

Furlong, J., & Maynard, T. (1995). Mentoring student teachers: The growth of professional knowledge. Psychology Press.

Furlong, J., Whitty, G., Barrett, E., Barton, L., & Miles, S. (1994). Integration and partnership in initial teacher education‐‐‐‐dilemmas and possibilities. Research papers in Education, 9(3), 281-301.

Tomlinson, P. (1996). Understanding mentoring. Reflective Strategies for School-based Teacher Preparation. British Journal of Educational Studies 44 (1):127-129

Wright, T. (Ed.). (2010). How to be a brilliant mentor: developing outstanding teachers. Routledge.

Wright, T. (Ed.). (2012). Guide to mentoring: advice for the mentor and mentee, ATL (available here)

Helen Harrison is the Primary strategic lead for Doncaster ITT Partnership, part of Partners in Learning Teaching School Alliance. She is currently a practising head teacher in a Doncaster school.

Helen Harrison is the Primary strategic lead for Doncaster ITT Partnership, part of Partners in Learning Teaching School Alliance. She is currently a practising head teacher in a Doncaster school.