David Darwent leads Post 16 Professional Practice modules and Mentor Training, and is a tutor to PGCE and Certificate of Education trainees in the Teacher Education Department in the Sheffield Institute of Education. In March 2017 he took up the post of Faculty E-learning Technologist, supporting the Sheffield Institute of Education to develop its e-Learning provision. In this blogpost he develops a conversation about approaches to mentors’ professional development.

David Darwent leads Post 16 Professional Practice modules and Mentor Training, and is a tutor to PGCE and Certificate of Education trainees in the Teacher Education Department in the Sheffield Institute of Education. In March 2017 he took up the post of Faculty E-learning Technologist, supporting the Sheffield Institute of Education to develop its e-Learning provision. In this blogpost he develops a conversation about approaches to mentors’ professional development.

Nurturing by nature or design: approaches to professional development of mentors

This week in the SHOOC we are looking at the nurturing aspect of mentoring, with particular reference to the period when mentees move on to another phase of their careers, whether that be with no mentor, a new mentor or the same mentor and irrespective of whether that phase-change has been long-planned or a sudden and unexpected move.

One key word from this week is reflection. We are looking at:

- mentors reflecting on their own practice and careers

- mentees being encouraged to reflect on their development

In the case study this week we have a reflective account of the first four years of one professional’s career which certainly wasn’t expected or planned to be as fast-paced as it has been and in that same interview we have learned about a powerful mentor – mentee relationships at a number of different career stages and about the impact that mentoring relationships have had on other areas of professional practice. Impact which was not planned nor anticipated but which – on reflection – has been transformational and substantial.

We’ve also asking the participants in the SHOOC this week to reflect on the past five weeks and consider what changes have happened in their thinking, knowledge, skills and understanding of being a mentor.

The learning stages of becoming a mentor

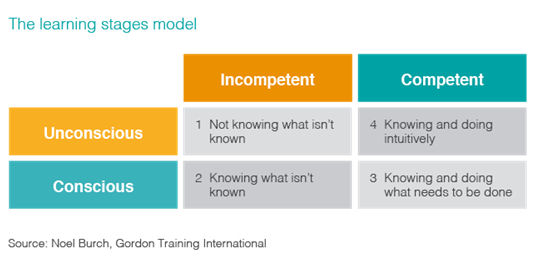

The other really major point I want to comment on this week is the cyclical nature of most aspects of mentoring and of career development and two cycles in particular come to mind: one is Noel Burch’s cycle of developing competence:

Although Burch presents this in a tabular form, I prefer to think of it as a spiral (or at the least a cycle) because we are all continually being unconsciously incompetent about something and equally we are all continually at each of the other stages of the model about something. If we focus on a particular aspect of our lives, the time to complete a cycle from unconscious incompetence to unconscious competence is likely to increase as we take on increasingly complex tasks – hence a spiral getting forever greater in diameter.

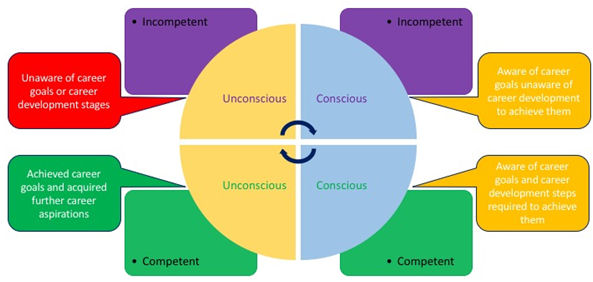

When anyone embarks upon a new career it is likely that they don’t know at the outset what their ultimate career goal is and it’s almost certain that they don’t know every step that will be required to realise their career goal. The process of discovering what goals are available / attainable and then working out how to reach them can easily be likenend to Burch’s model. I use this model to represent the phases of career planning and realisation.

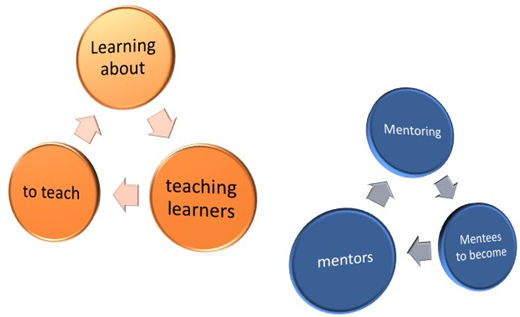

The other aspect to consider is the nature of mentoring mentees to become mentors (which we looked at briefly in the context of the role of the Senior Mentor Co-ordinator in any organisation) and similarities to the teacher-education process. Whenever we seek to show another person how to do a role we do ourselves we effectively enter into a teaching / mentoring / coaching / training relationship with that other person. Some of these – notably teaching and mentoring other teachers or mentors – tend to result in the teacher or mentor learning more about their role simply by carrying it out, i.e. by reflecting and evaluating and in turn the practitioners often then go on to seek others to teach or mentor them as they develop further, thus creating an endless process of forever learning about themselves.

Moderating and ensuring consistency

The ‘poor relation’ this week has been the topic of moderation and standardisation, which is again a reflective process and is always easier in organisations where there are many mentors and mentees who can collaborate. Moderation is also always at its most challenging in organisations where there is just one mentor and a very small number of mentees.

As I reflect on this week in particular, but the whole Enhance your Mentoring Skills SHOOC, I notice some emerging themes in contributions from some of our tutors and guest speakers and from our participants. One of the most powerful of these is the unpredictability of mentees’ needs and strengths; another is the highly predictable need for mentors to be very responsive and adaptable; and a third is the number of ways in which we all surprise ourselves when we reflect: and to this end I have surprised myself by making strong connections between my own current research interest in praise and feedback and the nurturing nature of the business of mentoring.

And that brings me back to the first part of this week, the reader, which began with that film of me, in my greenhouse, reflecting upon a reflective dialogue about the similarities between nurturing tender plants, nurturing learners (with reduced aspiration) and nurturing early career professionals who don’t yet know what they aspire to, still less how to achieve those elusive goals.

Further Reading

Standards for Teachers’ Professional Development (DfE, 2016)

Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teaching and teacher education, 27(1), 10-20.

Devos, A. (2010). New teachers, mentoring and the discursive formation of professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(5), 1219-1223.

Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., & Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and teacher education, 25(1), 207-216. (download)